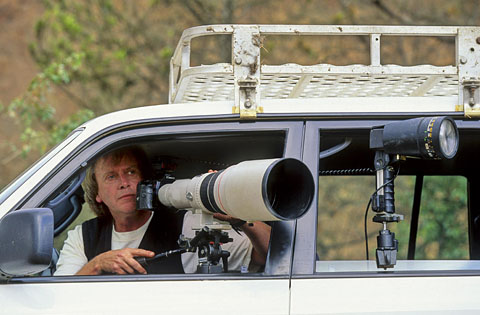

Interview with Nigel Dennis, Southern African Wildlife Photography Specialist

1. Nigel, you began photographing in 1980, concentrating mainly on the badgers and deer of the English countryside. Then in 1985 you decided to base yourself in Africa. Why did you move and when did you become a professional photographer?

I moved to Africa purely to attempt to fulfill a dream.

Opportunities for wildlife photography in the UK are somewhat limited whereas, of course, Africa offers huge diversity. I recall the first time I saw an aloe – and this is going to sound pretty daft to South African readers – and thought ‘Wow – what an amazing plant!’ During those first few years in Africa just about everything I saw was new, fresh and exotic to me.

I really was like a kid in a candy store and wanted to photograph everything I encountered in the natural world. During my first six years in South Africa I had to work at a regular job just to make ends meet.

I would rush off to the game reserves every weekend though and photograph right through my annual holidays. Even though I was working a five day week I managed to notch up around 100 days a year of photography – and began to build up a fairly comprehensive portfolio of African images. By this stage I was already selling my images through several stock agencies and steadily building a client base of my own.

The big leap to going full time pro came in 1991 and for that I really have to thank my wife, Wendy. Although I had a well paid job with a multi-national company I was becoming increasingly unhappy in the corporate world. Wendy said to me, "for goodness sake get out and let’s have a try at making a living from wildlife photography full time". The first couple of years were very tough but fortunately it has turned out pretty well in the longer term.

2. You then visited Southern African wilderness areas for 23 years before returning to the UK. Which area is your favorite and did you ever start taking the parks and their beauty for granted?

Like so many photographers I think I would have to say that the Kgalagadi is my favorite.

At times it is slow tough going but when everything comes together this Park can be outstanding. Although Wendy and I worked as far north as Madagascar and Zambia we spent by far the most time in Kruger and Kgalagadi.

No I don’t think ever I got to the stage where I took these two Parks for granted. I think it is possible to encounter a kind of ‘law of diminishing returns’ though. The easy stuff you get fairly quickly, after that it becomes increasingly difficult to find fresh or new opportunities.

The only thing I did become rather tired of was the same long old roads leading to these Parks. Both were a fairly long haul from where we lived in KZN.

3. The Kruger Park and Kgalagadi flora and fauna are probably some of the most photographed areas in South Africa. How do you get your work to be different to other photographers who are also regular visitors?

I think this is where working full time at photography offers a considerable advantage. Our average length of stay in a Park was around six weeks. This gives the opportunity to get a good fix on what is currently happening – particularly anything unusual.

Also we were able to build up a good working relationship with both Parks staff and researchers – a great help when targeting specific species.

Secondly in the early nineties I decided to make a bit of a paradigm shift in my photography. Instead of being primarily ‘subject driven’ I switched to what I like to call ‘light driven’ photography.

In other words I sought out fantastic light opportunities primarily and then looked for a subject in those favorable lighting situations. This way it is possible to make fresh new images of even the most common species.

4. Is there any location you haven’t photographed that you would really like to go to?

I would love to photograph wild tigers in Asia. Sadly I think I have probably missed that opportunity as so many of the Reserves have suffered terribly from poaching. Those that still hold viable tiger populations tend not to offer good photography. The place to get prime wild tiger images was undoubtedly Ranthambhore in India.

Way back in mid eighties the hugely talented German photographer Gunter Ziesler produced a superb book ‘Tiger – Portrait of a Predator’ (Collins, London, 1986) by working intensively there (the book still holds up well now if you can track down a second hand copy). But from what I have heard the Reserve is but a shadow of its former glory – so I have missed the boat on that one.

5. You have published 17 wildlife and nature books! With today’s new media methods of publishing - ebooks, DVDs and online tutorials - what path would you recommend someone take to publish their work?

Now you are giving me the tough questions, Mario! The ‘old’ way of getting published – in other words taking your concept to a publisher who fronts the design and printing costs, and the photographer then receives a royalty on sales – has become very difficult.

Far fewer wildlife books are getting published this way. Maybe it’s too early to say but my experience of DVD’s at any rate is that the return is not great. Online stuff like ebooks also may not produce as good a return – from what I have heard. Maybe that will change in the future though? You can of course self publish in printed format.

Risky though as the upfront costs are considerable and you need to be confident you have the marketing skills and contacts in the retail trade to sell the books. Not easy – I would approach that route with caution.

6. On page 169 of your book 'The Kruger National Park, Wonders of an African Eden', you have a superb photograph of a Pel's Fishing Owl. We have spent over 400 days in the Kruger Park and we've never seen one! What’s the most elusive animal you’ve had to photograph and how did you meet that challenge?

I have spent a great deal of time seeking difficult subjects, aardvark, pangolin, yes, the Pel’s, and an osprey catching a fish (but I never got that shot to work!).

I think the most physically demanding though was trying to get a half decent image of Madagascar’s largest living lemur, the indri.

Wendy and I spent two weeks tramping through Perinet Rainforest, along with a guide. It was not that hard to get a glimpse of an indri. Problem is they like the top canopy of the rainforest so the kind of view you usually get is looking straight up at the animal – all you see is two feet and a face peering down at you (hopeless for photography).

Groups of indri are on the move constantly, leaping from tree to tree - so of course we had to follow on foot. Perinet is quite hilly in parts, muddy and infested with delightful leeches. It was tough going with all the camera gear.

Eventually we figured out their routine and waited on a hillside where we thought we might be able to get a brief clear view at indri eye level when the group passed by. Result just one single image – after two weeks of photography...

7. You employ fill flash very successfully in your daylight photographs. This seems to be a technique that scares many photographers! How did you get it right? If a person visits the Kruger or Kgalagadi should they have the flash set up already in anticipation of having to use fill-light sometime in the day?

I think I get asked about fill flash more than any other subject. Firstly bear in mind you are just trying to add a little extra light to fill in annoying shadows or generally ‘lift’ the image a bit. So the golden rule is less is best.

As a broad guide I would mainly dial in minus one to minus one and a half stops on the flash setting. Often you might want to reduce the ambient light as well and so dial in say minus half a stop on the camera exposure. Unfortunately there is no strict formula to follow so there is quite a bit of guesswork.

Main thing is to learn from the pics that don’t work as you might have wished – and for sure I’ve had plenty of those! Yes it is helpful to have your fill flash set up the whole time – I have always worked like that.

8. How much of your time is devoted to ‘taking pictures’ versus the business side of things?

At my most active I guess I was photographing for about eight months each year. It was a case of six weeks in the bush, two weeks at home to edit, and then back out there for another six weeks, and so on. Since the digital era I spend a lot more time at home working on images, key-wording, etc. Not as much fun as being in the bush but it comes with the job description these days.

9. Photo equipment is important but some photographers are obsessed with having the latest body or lens. The camera manufacturers are partly to blame as their advertising says, 'if your photographs are just average then this new piece of equipment will change all that!' Where do you think a person wanting to improve their wildlife photography should focus their time, effort and money?

For anyone serious about their photography I think it would be a good investment to buy the very best equipment you can afford. Having said that, I would certainly not rush out and keep updating gear just because a new lens or camera body has come on to the market.

It would be much better to spend more time and effort in refining your photographic techniques.

Also photographing as frequently as possible is very important – even if it means keeping in practice by photographing at your local zoo or bird park, or just birds and bugs in your back garden.

10. Do you have any advice for someone who would like to make wildlife photography a career? Also what do you see as the future of wildlife and nature photography? Where do you think the skill is headed?

Those are also very tough questions, Mario. As far as a career in wildlife photography goes – my answer at this moment is very different from what I might have given a few years ago.

For many years we saw the market steadily change. The ease of generating large numbers of images very cheaply in the digital age is one factor. It means that the numbers of images being marketed on the Internet has grown exponentially during the last five or so years. This has of course tended to push prices down. We have also seen the so called ‘microstock’ online agencies arise – offering mostly amateur generated photography at ridiculously low prices.

So things gradually became harder for those making a living from photography. I think most professional photographers managed to adapt to these changes and continued to make a living. What caught us out (along with a great many investors!) was the 2008 recession. Since then the image market has been in steep decline – way beyond anything we anticipated.

I have been in contact with a number of other photographers, stock photo agencies and publishers - worldwide - to discuss the current situation. Most are of the opinion that things will improve as we pull out of the recession. It seems unlikely though that the image market will ever return to the pre-recession levels.

It will be much tougher to make a living from wildlife photography than in the past - but there will always be a demand for truly exceptional images. So as far as a career in wildlife photography goes I would advise anyone considering embarking on such a venture to wait out the recession. Now is the time to hone your skills and look at jumping into the market when things do eventually improve.

11. Do you have a strategy when going out on a photo safari? Do you plan a route the night before, do you go out looking for a specific animal, check the sighting boards, think in which direction you should be driving so that the sun is behind you, etc.?

Yes absolutely! If it’s a new location I will do a lot of research before the trip. Even for often-visited Reserves I draw up a ‘shooting list’ of subjects I want to target. I even go so far as making rough sketches of the kind of images I want to achieve.

When I arrive at a Reserve I start off by having a chat with the Parks staff to find out the latest info. This may mean I revise or add to my ‘shooting list’. Always though I think better results are achieved by going out with specific objectives, rather than just driving around and hoping to find something good to photograph.

12. What do you think about video in the new DSLR cameras, and how do you see it impacting wildlife photography?

My guess is that the DSLR’s started as a way of shooting both stills and video without having to carry two lots of equipment. Very handy for holiday stuff.

The video function has improved greatly now of course. I think it may be a little early to tell how this will impact on pro photography.

Maybe it will be the next big thing? In which case us stills photographers will be on a steep learning curve! Producing commercial quality video is a hugely different skill from stills photography.

13. Your books and photographs have been an inspiration and have encouraged many people to take a greater interest in nature, photography and the environment. With who and where you are today, what does it take in an image to inspire you?

Here I’m reminded of the very old photographer’s joke:

Q. How many photographers does it take to change a light bulb?

A. One hundred. One to actually change the light bulb, and ninety-nine to say ‘Well of course I could have done that!’

So the images that really inspire me these days are those where I think ‘Wow! I would never have thought of tackling the subject like that!’ It’s all about pushing the boundaries to get a fresh, inspired image.

14. In conclusion, Nigel, how about three 'top tips' photographers could use to capture better wildlife images?

Maybe the most useful tips I can give are the three stages or steps I go through every time I photograph any subject anywhere. They work for me so I hope they may prove helpful to others:

Step One: Ask yourself ‘Is there anything fundamentally wrong with the image I can see in the viewfinder?’ I’m talking really basic stuff here such as a tree in the background appearing to grow out of the top of a lion’s head (I think we have probably all been caught out by this one – I have!).

Also look around the edge of the image – see if any distracting clutter can be avoided by framing the picture differently. Of course these days we can fix a lot of these problems later in the digital darkroom. I think however it is far better to start with a fundamentally sound image rather than spend ages later at home trying to patch up basic errors with Photoshop.

Step Two: Take a few shots. These are ‘insurance pics’ – just in case the subject runs away or flies off. Not a concern with flora or landscapes of course but I still take a few shots in any case. These ‘insurance pics’ are important as they break the psychological barrier of wanting to get something ‘in the bag’. Then we can move on to having fun and getting creative.

Step Three: Is all about asking yourself ‘How can I make this image better?’ Play around with composition, lighting and exposure. If possible, try different camera angles – not just moving left or right but also a lower or higher camera position.

Try framing the image vertically as well as horizontally.

Try different lenses from a wide angle to your longest telephoto (if you are close enough, shots of just the eye of the animal or bird can be striking). I could go on and on here as the possibilities and permutations are pretty much infinite.

It’s all about taking chances. Don’t worry about making ‘mistakes’ – that is how we all learn. The main thing is to push the boundaries – that is the path to making fresh, striking new images.

About Nigel Dennis...

Nigel's photography has appeared in many of the world's top magazines including National Geographic, Time, and Geo. Nigel's images have been published in over 25 countries world-wide.

To date he has produced seventeen wildlife and nature

books.

His

web site features a vast range of Nigel’s images.

All images on this page © Nigel J Dennis

Return from Nigel Dennis to Interviews Page

To make a safari rental booking in South Africa, Botswana or Namibia click here

"It's 764 pages of the most amazing information. It consists of, well, everything really. Photography info...area info...hidden roads..special places....what they have seen almost road by road. Where to stay just outside the Park...camp information. It takes quite a lot to impress me but I really feel that this book, which was 7 years in the making, is exceptional." - Janey Coetzee, South Africa

"Your time and money are valuable and the information in this Etosha eBook will help you save both."

-Don Stilton, Florida, USA

"As a photographer and someone who has visited and taken photographs in the Pilanesberg National Park, I can safely say that with the knowledge gained from this eBook, your experiences and photographs will be much more memorable."

-Alastair Stewart, BC, Canada

"This eBook will be extremely useful for a wide spectrum of photography enthusiasts, from beginners to even professional photographers."

- Tobie Oosthuizen, Pretoria, South Africa

Photo Safaris on a Private Vehicle - just You, the guide & the animals!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Please leave us a comment in the box below.